[ad_1]

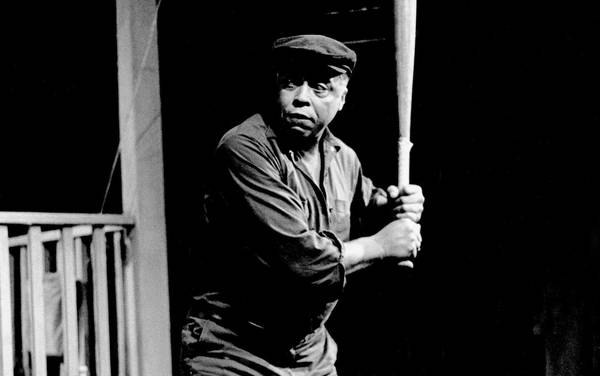

Opening night, 1986. August Wilson’s play “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone”, Huntington Theater Company in Boston. Patti Hartigan, a rising young critic and arts writer, took her seat for a pre-Broadway test performance, one of the regional theater stops for the new pre-Broadway play.

Hartigan will never forget what he saw that night for many reasons, most notably the climax of Act 1: The image of a haunted man, bones walking on water, consuming him in the middle of a jolly Pittsburgh hostel celebration. These are the bones of enslaved Africans lost in the Middle Passage. Wilson’s play takes place in 1911. America’s former slaves are free on paper, but they are searching for it by following the scent of what Wilson calls “blood memory.”

In his gripping, richly detailed biography “August Wilson: A Life,” recently published by Simon & Schuster, Hartigan calls “Joe Turner” Wilson’s greatest achievement. He has many friends of this opinion.

For much of the 1980s and ’90s, Wilson worked like a one-man vaudeville touring show: a man, a typewriter, and one more play in an ambitious 10-play cycle of 20th-century Black American life and poetic drama. Wilson developed and revised (and cut and cut) his plays for a wide network of nonprofit theaters, including Chicago’s Goodman Theater. The goal was a commercial debut on Broadway; sometimes it was profitable (“Fences”, “The Piano Lesson”), other times it was not very successful (“Joe Turner”) or even close (“King Hedley II”, “Ocean Stone”, “Radio Golf”). Money is not everything. Games are constantly ready to be revived and reevaluated.

In 1982, Wilson was having his second of three marriages, Minnesota, St. O’Neill had presented plays to the National Playwrights Conference five times in five different years. His sixth presentation “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” paid off. And then August Wilson became a force slowly, then quickly.

Conference director Lloyd Richards, the first Black director on Broadway (Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 film “A Raisin in the Sun”), even saw something in his four-hour nascent furry in “Ma Rainey.” Next, the bell curve of the famous 12-year writer-director partnership stretched from 1984 to 1996 on Broadway. The behind-the-scenes drama of Wilson’s greatest Broadway success comes vividly to life in Hartigan’s book, along with Wilson’s extraordinary family history. There is enough Wilson, personality, difficulty, setbacks, and success to detail Hartigan’s history, which includes many parts of a great American playwright.

Wilson died of liver cancer in 2005 at the age of 60, five months after finishing his last work, Radio Golf. Hartigan’s book tour brings him to Chicago on August 22 for a discussion and book signing at the American Writers Museum downtown.

Our interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q: Your book begins in 2003, two years before Wilson’s death, when he returned to Pittsburgh for the funeral of his friend Rob Penny. According to some of his former Pittsburgh adherents, Wilson was, as you’ve written, “the one who turns his back on the community.” Penny did not and did not want to speak at Wilson’s funeral. Can you get into that for us?

A: I rewrote that preface probably a hundred times. I wanted to capture a moment of August when he was at the height of his fame and came back to where it all began, that church in the Hill District of Pittsburgh. For someone as important as himself, success changed the way many people view him. He was empathetic enough to feel it. It was he who really succeeded, and many people thought that someone else would. No one thought August would actually pass.

When I was talking to someone the other day about Angela Duckworth’s book “Grit,” August Wilson came to mind. He had the courage. He came from nothing. He has a genius-level IQ but dropped out of high school at the age of 15 (after years of racial taunts at the toughest Catholic schools he went to). Grit sometimes has a price. I think August was the guy who still hangs out on top with Gabriel (a character in “Fences”) and Hambone (“Two Trains That Run”) at heart, yet he was there, city to city at the premieres. The guest of honor who prefers to talk to the waiters.

Q: Can you talk about your excavation for the preface to the book that takes us to Wilson’s mother’s family in Spear, North Carolina?

A: August always told people that his mother was born on a mountain in Spear, and that was true. He never went there himself, and his mother and siblings never came back, just as my grandparents never came back after they left Ireland after the civil war. I was interested in this. August’s cousin, Renee Wilson, has been researching their family history for years and shared some of what she learned. The two of us went to Spark and climbed the mountain with a local guy running around those mountains (Southern Appalachia). He took us to the farm of Sarah “Eller” Cutler, August’s great-grandmother. (They were the only Black family on the mountain, as Hartigan wrote in the chapter entitled “Memory of Blood.”) Cutler was in a relationship with Willard Justice, a white farmer who lived nearby. Their stories are fascinating and nearly 100 years later the farmhouse was still there! January was still there. It was astonishing to see this with August’s cousin.

Q: There is a wonderful story in the book where Wilson met a librarian at the University of Pittsburgh library when he was a teenager —

A: Thanks for saying that! I know you know August as well as I do. Doesn’t that reflect his personality? The idea of befriending the woman in the library, someone who can buy her all the books she wants, and then exchanging “word of the day” every time they see each other? Great insight into young August Wilson.

Q: You write a lot in your book about the most important father/son relationship in Wilson’s life, albeit a metaphorical one: his relationship with director Lloyd Richards, who gave him a chance to start. Wilson’s plays, especially “Fences” and “Jitney”, are filled with these harsh father/son portrayals. Richards’ work as director has been documented as crucial to the final outcome of Wilson’s early plays and greatest achievements as script editor and dramaturg. And Wilson began to resent the relationship.

A: In the book I say that both are right and both are wrong. It was like a divorce, but perhaps inevitable. Theirs was a symbiotic relationship. Both have gained a lot. It was tragic to end, but as it went on, one of the most important relationships in American theater, he was there with Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan.

Q: I’m absolutely naive financially, but I didn’t realize how much of their disagreement was due to lawyers fighting over percentages on contracts.

A: It’s part of the job, but it also goes to a deeper father/son (conflict) point. Anyone could see that August wanted more control. After “Fences”, when he nearly lost control of his own game (producer Carole Shorenstein Hays and lead actor James Earl Jones agitated for major script changes), he wanted to be more responsible. of everything. And at least in part to make the decisions that the director normally makes. And you don’t do that with Lloyd Richards.

Q: He wasn’t exactly unique in this regard, but the more successful Wilson was, the less time he spent long distance getting his games in shape. “Two Trains Running” I remember interviewing him in Seattle on his way to New York via San Diego. And he said, more or less suddenly, that he never really emptied his schedule to give himself a few weeks of solid writing time on that game. “I never got my bear,” he said.

A: When you’re so busy and promised to the theater world, to your mother, to yourself that you’ll write this cycle of 10 plays – that’s a huge burden to carry every day. He had to finish those 10 games, but he still had this grueling, mind-blowing schedule. He almost never came home. Everyone wanted a piece of him. And then in 2005 the man dies and he has to play his last game “Radio Golf” no matter what. This is huge pressure.

But look what he’s accomplished. Even the most problematic games have something. You look at “King Hedley II” (which made a pre-Broadway stop on Goodman in 2000) and the monologue of Viola Davis playing Tonya? About why she couldn’t bring another baby into the world? If that was the only thing in that game, it still deserves a place on every shelf, she.

Hartigan will discuss “August Wilson: A Life” with actor and playwright J. Nicole Brooks on August 22 at 6 PM at the American Writers Museum, 180 N. Michigan Ave. americanauthorsmuseum.org

Michael Phillips is a Tribune critic.

twitter @phillipstribune

[ad_2]

Best American Comics News bestamericancomics.com started its broadcasting life on December 21, 2022 and aims to offer original content to users. Aiming to share information in technology, science, education and other fields, bestamericancomics.com aims to provide its readers with the most up-to-date and comprehensive. Since the content of the site is created by expert writers, readers are reliable and accurate referrers.

Best American Comics News bestamericancomics.com started its broadcasting life on December 21, 2022 and aims to offer original content to users. Aiming to share information in technology, science, education and other fields, bestamericancomics.com aims to provide its readers with the most up-to-date and comprehensive. Since the content of the site is created by expert writers, readers are reliable and accurate referrers.