[ad_1]

Monee’s old town is only a few blocks wide, but thanks to “The Cut” you may not be able to see from one end to the other.

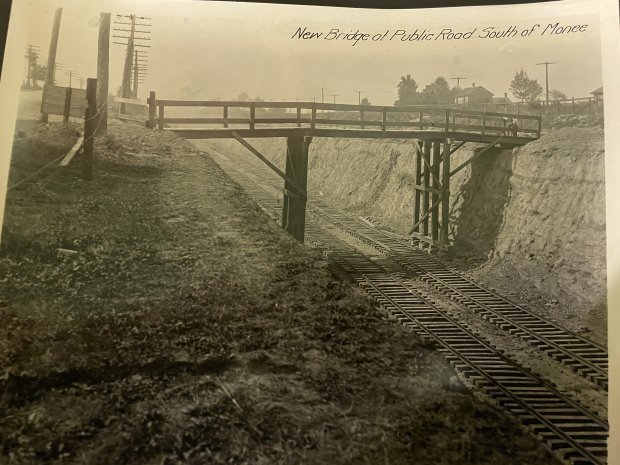

The Cut, a 25-foot-deep and 83-foot-wide man-made valley that runs the length of the town, celebrated its 100th anniversary last year. A prominent feature in the village. However, there was no celebration.

It was born as a railroad town when the Illinois Central established a station near Raccoon Grove in the 1850s; This area was transferred to Raccoon Grove’s descendants by treaty. Indiana fur trapper Joseph Bailly and his wife MarieA. member of the Ottawa Tribe person identified as “Mo-nee” in many contemporary documents.

It was a high place, a hill above a glacial moraine It was formed during the final stages of the last ice age, and a thriving town grew around the depot, providing direct access to Chicago. Dairies were established to process dairy products and send them to the north. Grain elevators lined the tracks, and in the 1920s four banks were established in the village, with the name Monee in 1874.

“We were one of the most populous, most established and most vibrant cities in the 1850s and ’60s,” said Christina Holston, president of the Monee Historical Society.

“We became victims of our own success.”

When the Illinois Central built its warehouse at what would become Monee, it wasn’t because of the views the high ground offered. On the contrary, the locomotives nearly ran out of steam after completing the long, steep climb, and water towers were installed at both ends of the young town, along with housing for the crew.

The demand for water outstripped the supply offered by a series of small ponds, and by 1916 the steam engines’ thirst was quenched by water from a much larger reservoir the railroad dug west of town in what is now one of Will County’s Forest Preserves. premier fishing features.

There were many trains to supply together “The Main Line of Central America” A rail line connecting Chicago to the Gulf Coast. Decades later, in the days when mass rail travel was fading, it would inspire Steve Goodman’s hit song “City of New Orleans.”

“In the 20s, there were 1,100 freight trains a month and 23 passenger trains a day,” Holston said. That’s incredible.”

There were several roads in Monee, but only two main roads ran through it. And the steam engines running uphill there could only carry so much. Monee’s hustle and position at the top was clogging up the system.

“This was a bottleneck,” Holston said.

In the early 1920s the Illinois Central was good at moving soil. A series of agreements with leaders in Chicago had gradually upgraded the rail line there from a trestle bridge across Lake Michigan to a sunken street surrounded by parkland above.

IC officials agreed in 1919 to eliminate most of the level crossings in the city by raising the tracks and building new buildings. viaducts for the streets below while implementing the infrastructure to electrify its entire fleet, starting from commuter rail line to the southern suburbs.

Railroad companies were rich and powerful in the early years of the 20th century. They could afford huge engineering projects and received government assistance in the process. But astute observers in the industry knew dark clouds were forming over Detroit, where automakers were bringing individual transportation to the masses, unconstrained by rails and tariffs.

One way to improve efficiency was to straighten the course, smoothing out any bumps that slowed the steam engines and required them to reduce tonnage to make the grade. Another benefit was the elimination of slowdowns and stops at intersections due to collisions with people, animals, and, increasingly, motor vehicles.

And IC knew how to do it. Rails have been upgraded in many places. As the land gradually rose from the bed of ancient Lake Chicago in Homewood, the tracks remained at ground level while viaducts were dug beneath them for cross-traffic. The tracks were re-elevated at Matteson and Richton Park as the ground dropped southward, before being re-elevated at University Park, the end of the line for modern commuter service.

As early as 1891, the railroad purchased land in what would become Flossmoor, with plans to excavate the soil, load it onto trains, and ship it to Chicago, where it would lay support lines to serve the upcoming Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park.

But the Flossmoor soil was too rich in clay, not crumbly enough for the IC’s purposes, and was instead used to raise the rail bed there. The Flossmoor Road viaduct was installed in 1912 and the remainder of the land was subdivided into parcels. The railroad built model homes along Sterling Drive and attracted potential buyers with excursion trains from Chicago that included free lunches.

Illinois Central had different plans for the bottleneck at Monee. Instead of creating buildings, it would replace nearly the entire business district.

After digging The Cut, trains could zip through town unimpeded, from the flat plains of Illinois to the straight line north.

“They didn’t have to slow down or stop,” Holston said. “It made a huge difference to their well-being, but the entire business district was there. One side of the tracks was Chestnut, the other side was Oak, and all the businesses were up and down these two streets. “They had to carry them when they inflicted that big wound on the town.”

The old warehouse was demolished and a new warehouse was built 25 feet down at The Cut. Grain elevators had to move. Dairies are closed.

“It really affected it, it killed the growth of the town,” Holston said. “20. It stagnated for the rest of the century.

“It wasn’t that long ago that passenger trains no longer stopped at Monee.”

The new depot at The Cut was demolished and eventually the rails through Monee were reduced to single track.

“The trees have now grown so much that you cannot even see from one side of the tracks to the other,” he said. “So the town is actually two towns.”

On the west side is Illinois Route 50, where a few restaurants and bars have operated over the years but have not generated much foot traffic. Interstate 57 emerged in the mid-century and eventually attracted the attention of off-ramp development.

On the east side of The Cut, “there wasn’t much in my living memory,” Holston said. “When the train crashed, most of the business died with it. People can get in their cars and go to other places. There was no quid pro quo, no tit-for-tat. “That is dead and not much has taken its place.”

Most of the surviving structures were converted into homes, and many still survive on Oak, Chestnut and Main streets. Monee has embraced its bedroom community status in a big way.

“We love it the way we love it and we love being a small town,” Holston said. “This was the thinking of the town fathers for much of the 20th century.”

In 2011, an effort to prevent the demolition of a structure that predates The Cut, a limestone barn on Court Street that long ago housed one of Monee’s dairies. Monee Historical Society. At the dairy, now renamed the Monee Heritage Center, Holston and her fellow volunteers are trying to reclaim some of Monee’s lost history.

“There are 4-5 houses whose history we know. “We want to do more research and at least learn the dates in order to raise awareness about our history,” he said. “There was never a historical society at Monee until 2011, nor was there an organized effort to collect data and artifacts. “Everything we’ve done has been done in the last 12 years.”

That’s why they’re collecting the brightest stories before The Cut and slices of life after it. There are tales of revelry and depravity at the dance halls and party venues around Raccoon Grove, a destination popular enough to merit a stop on the intercity trolley line from 63rd Street in Chicago.

The town cemetery created a potter’s field section because “every time you turned around, someone was falling off the train or walking in front of it.” “Those were tough days; there weren’t a lot of safety measures,” Holston said.

And there are stories about how The Cut was carried out in 1922 and ’23. Holston said he collected anecdotes about how farmers were hired to bring teams and wagons to haul material, and how much of the excavated material was taken “directly toward Richton Park and Matteson,” where the tracks were elevated. “This is Monee shit.”

Some remember how the Model T Ford was able to fit on an old pedestrian bridge on The Cut that had collapsed, and the public excitement and outcry when the bridge, a popular meeting place especially among young people, was removed in 1989.

But as far as he understands, the IC faced no opposition when it brought the idea of The Cut to the city more than a century ago.

“It was Goliath and David,” Holston said. “Monee is just Monee. He didn’t stand a chance against the wheels of progress like this. “I feel like a few people have their hands greased, but I doubt most people understand what the long-term consequences will actually be.”

If they had fought, everything could have turned out differently.

“If it had lasted another 10 years it probably wouldn’t have been a problem because right after that the diesel engines started coming in,” he said.

Landmarks is a weekly column in which Paul Eisenberg explores the people, places and things that have left an indelible mark on the Southland. He can be reached at peisenberg@tribpub.com.

Best American Comics News bestamericancomics.com started its broadcasting life on December 21, 2022 and aims to offer original content to users. Aiming to share information in technology, science, education and other fields, bestamericancomics.com aims to provide its readers with the most up-to-date and comprehensive. Since the content of the site is created by expert writers, readers are reliable and accurate referrers.

Best American Comics News bestamericancomics.com started its broadcasting life on December 21, 2022 and aims to offer original content to users. Aiming to share information in technology, science, education and other fields, bestamericancomics.com aims to provide its readers with the most up-to-date and comprehensive. Since the content of the site is created by expert writers, readers are reliable and accurate referrers.