[ad_1]

Turtel Önli placed a pile of books, some mail and his bag on the table. He leaned in and raised his eyebrows somewhere between caution and politeness, saying: “I hope you’re saying in this article that I’m still publishing, I’m still here, and I’m still an advocate for black artists in comics. The exhibition I was at at the MCA a few years ago? ‘Chicago Comics.’ Remember this? This program could also be called ‘Chris Ware and Friends’. I appreciate that my character, NOG, is on the wall of the museum like a billboard for the exhibition and on the tote bags for the show. But you know what, I didn’t get a single professional phone call from anyone who watched that show? Not the galleries, not the publishers, not anyone. Plus, people talked about me in articles (about the show) like I was dead and gone! ‘Oh, such a shame for Turtel, how he always gets overlooked…’”

But I said, you’re always overlooked.

“Yes,” he said, “yes, I know. But look at me now, that’s what I’m saying.”

We sat at Café Logan, part of the Logan Center for the Arts, on the south end of the University of Chicago campus in Hyde Park. We chose this location because Onli has a new exhibition in the cafe – which only serves to underscore the fact that Turtel Onli, the pioneering comics creator and one-man social network, remains obscure, literally overlooked: Even though the cafe is full of students, nearly everyone was hunched over their laptops, inches from their heads, showing no signs of even noticing his handiwork.

When I entered the cafe, my first thought was:

“Can someone give this guy a decent show?”

“You have to say that in the article,” he said.

Turtel Onli was looking to break into the world of mainstream superhero comics in the 1970s and 1980s. He was working as a courtroom artist for WGN-TV and as an illustrator for Chicago magazine, Ebony and Playboy (then still based in Chicago). He went to Paris and made illustrations for the English-language newspaper Paris Metro. He would go on to design album covers for many R&B and rap artists, including George Clinton and Kurtis Blow; He was even briefly commissioned by the Rolling Stones to do the cover of their 1978 album “Some Girls.” (“They wanted something absolutely offensive. So I gave it to them. The lawyers wisely stepped in to say, ‘You can’t show that.’) His art was collected by Alice Coltrane and Miles Davis. Still, DC and Marvel said no.

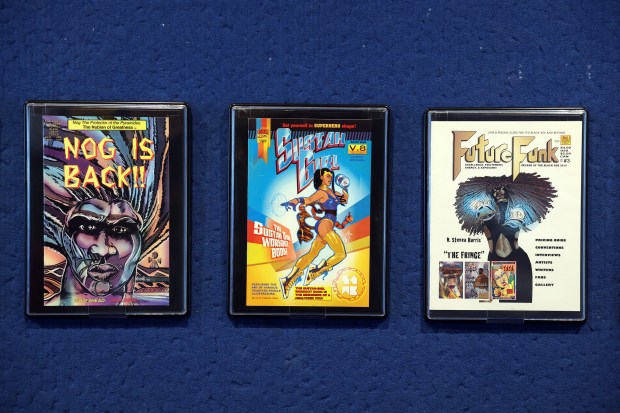

So in 1981, Onli, who grew up in Hyde Park and Albany Park, published a comic book starring his own hero: NOG, Guardian of the Pyramids. He sold it at art fairs and headshops. He continued to self-publish more comics, as well as self-help books on exercise and the zodiac, sold as works by Onli Studios. He never left his field of curiosity.

Style probably has something to do with it.

Imagine the psychedelic cacophony of 1960s Jack Kirby Marvel comics meets the 1970s bravado of Heavy Metal magazine, the custom van decor, the fancy obsession of your ninth-grade friend who drew in school binders all day long.

“Turtel jumps in with both feet, making you turn your head to the side and wonder what exactly you’re seeing,” laughed Decatur-based Afua Richardson, who first encountered Onli nearly a decade ago. It put him in touch with other Black comic book creators, and he soon began drawing covers for both Marvel and DC. He recently drew the character Spider-Punk in the Oscar-nominated movie “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse”.

“I think Turtel was trying to appeal to older Marvel and DC guys at first, and Marvel and DC had house styles. “And if you weren’t creating like Kirby, they wouldn’t let you join the club,” he said. “Turtel’s work is largely fine art, but it’s also comic book art.”

Richardson added: “Moreover, it started at a time when few people thought of futurism and Africa in the same sentence, and it did. Even though it wasn’t very popular, he brought African aesthetics to comics. And that’s a whole other thing: When I started, if I had a hair out of place, I thought, ‘Can we make this less urban?’ you would hear.

Onli was a Black comic artist trying to break into an almost entirely white industry, and in a very specific way. He casually refers to his style as “Rhythm,” assuming you understand. What he means is that art created with African and European influences and a dazzling splash of fantasy evokes past and future. However, he insists that it is not Afrofuturism.

“I think my work is rudimentary for the future,” he says. “Basically, ‘primitive’ as it is. If their cultural and artistic roots are weak, there are standards that exist before us. It is also experimental. From a black perspective, it deals with the idea that we are Western in this country but there is a separation – but I still have genetic memory and a lot of cultural continuities, and when I work those things can flow outward.

I understand?

He would explain this to middle managers who needed someone to draw Iron Man and Green Lantern. “Do black people understand science fiction?” and “Are black people reading?” He told me: “It would be disturbing because I would look at them like: OK, these people need help. This was also a strange situation because they saw the name ‘Turtel’ on the meeting list and had no idea who or what I was. Also, NOD had dreadlocks, which wouldn’t be a problem if you were Bob Marley. Not superheroes. He was defending a black planet. ‘Wait, isn’t he taking over the KKK?’ I used to hear something like this. No, this is not about prison life, struggle, affirmative action, or thug life. I would say, ‘He defends a planet, not a village, or even a secret country,’ like Black Panther. And that was unheard of.

Luke Cage mostly defended Harlem; Black Panther mostly wandered around Wakanda.

Onli would work for this money, and he once said he was offered a $20,000 check for NOG (he declined to name the publisher), but “they were going to have everything and lock me up for 10 years.” I was a fool. I didn’t know any better. I had no mentor. I was making better money at Playboy and Ebony, and I broke that check into molecules.”

Of course, Onli was not alone in this disappointment, and in 1993, with the help of several other aspiring Black comics artists, he declared this period the “Dark Age of Comics,” emulating Marvel and DC practices. they repackaged their blockbuster history into the Golden (1938-1950), Silver (1956-1970), and Bronze Comic Book Ages (1971-1985). Onli co-created the first Black Comic Age Convention at the South Side Community Center. Nearly 1,000 artists and fans attended and networked. Shortly thereafter, artist Dwayne McDuffie (died 2011) co-founded the Black-based Milestone Comics, published by DC. Dark Age of Comics conventions continued for decades and inspired similar “Black Age of Comics” gatherings in New York City, Detroit, and Georgia.

But Onli remained in Chicago.

He drew more and more comics; He produced works like Spike Lee’s “Malcolm-10,” which echoed his popularity in the early ’90s and featured a genetically engineered vigilante who tracks down drug dealers and gang members and sends them to their deaths. Rhythm Zone.

Onli is now 72 years old and said he started his career at 18, but in reality it was earlier. His grandfather was a Chicago preacher, Reverend Samuel Phillips. “He was born in the 1800s and was known for drawing large images of the Bible that he would use in his sermons. He was working on these in the apartment we lived in, his three sons were drawing at the table, and they allowed me to join in.” The biblical scenes his grandfather painted on oilcloths and window shades would become well known in outside art circles.

He said the only thing he cared about as a child was art. He would introduce himself as an artist in primary school. He was also good at basketball, “but when I asked my parents to sign papers for a basketball scholarship, they wouldn’t sign and I got upset, so I was told I was ungrateful and had a few months left at home. When those months were over, I kissed them and never went home again. I was raised by my grandparents and attended Calumet Township High School (in the Gresham neighborhood of Auburn). He later attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and sold his first painting at 19 to Johnson Publishing, which needed art for its new building on South Michigan Avenue.

He went to France for a while, hoping his comics would find a better home. She returned and worked as an art teacher and clinical art therapist in Chicago Public Schools. These days, he teaches art appreciation and drawing at Harold Washington College. He uses himself as a lesson. Certainly his work is diverse and fluid, as if each image was cut from a larger, giant mural. Dan Nadel, who curated the MCA exhibition, said he was attracted to Onli’s art because “he starts with cultural identity and builds fantasy and heroism from that foundation.” He thinks of these as “consciously assertive approaches” to the familiar.

This translates into a cult fandom so small that the only place to buy its comics in Chicago, other than Onli’s website, is the gift shop at the DuSable museum.

“I feel like I belong, but no one understands,” he told me.

He looked around the café filled with art.

“The beauty of this show is that all these young students are here. But the problem is, they don’t always turn around and see what’s hanging on the wall behind them.”

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com

Best American Comics News bestamericancomics.com started its broadcasting life on December 21, 2022 and aims to offer original content to users. Aiming to share information in technology, science, education and other fields, bestamericancomics.com aims to provide its readers with the most up-to-date and comprehensive. Since the content of the site is created by expert writers, readers are reliable and accurate referrers.

Best American Comics News bestamericancomics.com started its broadcasting life on December 21, 2022 and aims to offer original content to users. Aiming to share information in technology, science, education and other fields, bestamericancomics.com aims to provide its readers with the most up-to-date and comprehensive. Since the content of the site is created by expert writers, readers are reliable and accurate referrers.